Typewriter History

Since the fourteenth century, when the idea of writing machines became technologically feasible, more than one hundred prototype models were created by over 50 inventors around the world. Some of the designs received patents and a few of them were even sold to the public briefly without much success. The first such patent was issued to Henry Mill, a prominent English engineer, in 1714. The first American paten for what might be called a typewriter was granted to William Austin Burt, of Detroit, in 1829.

However, the breakthrough came in 1867 when Christopher Latham Sholes of Milwaukee with the assistance of his friends Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule invented their first typewriter. Sholes’s prototype model, which is still preserved by the Smithsonian Institution, incorporated many if not all the ideas from the early pioneers. The machine "looked something like a cross between a small piano and kitchen table" as one historian observed. However, the breakthrough came in 1867 when Christopher Latham Sholes of Milwaukee with the assistance of his friends Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule invented their first typewriter. Sholes’s prototype model, which is still preserved by the Smithsonian Institution, incorporated many if not all the ideas from the early pioneers. The machine "looked something like a cross between a small piano and kitchen table" as one historian observed.

Despite the importance of Sholes's improvements in the machine's mechanical workings over the next several years, the story of the typewriter from 1868 to its booming success in the late 1880s is really the story of its staunchest supporters, James Densmore and George W. N. Yost. The result of Sholes’s efforts was recognized by the two entrepreneurs as being of particular merit and they purchased Sholes’s patents for about $12,000 – a significant sum in that period. Densmore and Yost succeeded in convincing E. Remington and Sons at Ilion, New York, which was making fire arms, sewing machines and farm machinery and was looking for new products to manufacture.

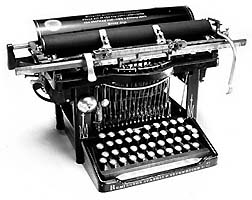

In 1873, Remington singed a contract with Densmore and Yost to develop the first practical commercial typewriter and the first shipments were made in 1874. The first Remington model, known as Sholes and Gliden Type-Writer, was engineered by Remington’s two great mechanics from its sewing machine division. The original Shoes model, for the most part constructed of wood, was used a masterpiece by E. Remington and Sons and from this was produced the first practical commercial typewriter. The appearance of the first typewriter, which bears little resemblance from Sholes’s prototype, naturally looked a lot like a sewing machines, with a foot-pedal carriage return of sewing machine design and charming flowers stenciled on the black metal front and sides.

The Sholes and Gliden model, wrote capitals only, is the first for introducing the QWERTYT keyboard, which is still used in computer keyboard of today. The typing mechanism of the first model is referred as an "up-strike" design. Pressing on the key swings the type-bar up toward the platen. This means that a typist can not see what has just been typed and for this reason the machine is called a "blind-writer". The Sholes and Gliden model, wrote capitals only, is the first for introducing the QWERTYT keyboard, which is still used in computer keyboard of today. The typing mechanism of the first model is referred as an "up-strike" design. Pressing on the key swings the type-bar up toward the platen. This means that a typist can not see what has just been typed and for this reason the machine is called a "blind-writer".

The establishment of a market for writing machines was the next great obstacle in the path of the promoters. Practically no one was interested in paying $125 for a typewriter. The first Remingtons were shipped right back for further adjustment. Few businessmen could be found who believed that the introduction of typewriters in their offices would be practical. One reason given was that many employers felt typing would appear rude to customers for lacking of personal touch. Another obvious reason was that the first typewriter was extremely difficult for anyone to type in a speedy way as it was intended due to mechanical imperfections. This reason was exemplified by the experience of Mark Twain, who bought the first typewriter but later regretted for doing so.

The promoters were forced to adopt a policy of lending a machine to each of several hundred business houses in the hope that someone would find time to practice. They also had the full belief that this practicing would convince a number of people that a saving of time, as against handwriting, was possible. It wasn't until 1878, when Remington introduced its model No. 2, a reliable and efficient writing machine was born. It had the look of a modern typewriter in black enamel paint. The No. 2 typed both upper and lower case thanks to the invention of a shift key. However, it took nearly a decade for the Remington No. 2 to become the first successful commercial model, and the typewriter industry was on its way. The promoters were forced to adopt a policy of lending a machine to each of several hundred business houses in the hope that someone would find time to practice. They also had the full belief that this practicing would convince a number of people that a saving of time, as against handwriting, was possible. It wasn't until 1878, when Remington introduced its model No. 2, a reliable and efficient writing machine was born. It had the look of a modern typewriter in black enamel paint. The No. 2 typed both upper and lower case thanks to the invention of a shift key. However, it took nearly a decade for the Remington No. 2 to become the first successful commercial model, and the typewriter industry was on its way.

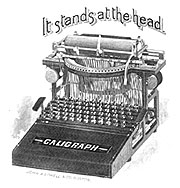

The success of Remington’s first practical machines stimulated invention during the years which followed, and it was that other plans of construction should develop. Each inventor had his own ideas and theories with respect to basic principles of writing machines and the goal was to produce a better and faster and cheaper alternative.

Before 1890, three distinct classes of typewriters had been developed and extensively used. One of these was the Hammond with all the type on a wheel and equipped with a double shift for capital letters and figures. Another class was equipped with a double keyboard for upper and lower case. While a double keyboard allows an operator to access all characters without using a shift key, the operator had to learn the position of a different key for both small letters and capitals. A third class, representing the most popular, was that which incorporated in individual type bar principle with a single shift keyboard, each bar carrying two type faces, small and capital letters. This popular construction, however, still lacked the vial quality of visibility, of allowing the operator to see each character as it was printed. Before 1890, three distinct classes of typewriters had been developed and extensively used. One of these was the Hammond with all the type on a wheel and equipped with a double shift for capital letters and figures. Another class was equipped with a double keyboard for upper and lower case. While a double keyboard allows an operator to access all characters without using a shift key, the operator had to learn the position of a different key for both small letters and capitals. A third class, representing the most popular, was that which incorporated in individual type bar principle with a single shift keyboard, each bar carrying two type faces, small and capital letters. This popular construction, however, still lacked the vial quality of visibility, of allowing the operator to see each character as it was printed.

In the early years of typewriter history, the understroke or blind-writing machine had such widespread use and acceptance that few looked for any radical change in construction. When Remington introduced its improved Model No. 2, one advertisement quickly declared that there was no longer ay achievement left for the typewriter industry, because this model was everything the machine could be. But as always, there were a few individuals who reasoned that the capacity of the typewriter could be vastly increased by some new arrangement of type bar action, which would allow the actual printing to be done in full view of the operator. This would eliminate the great inconvenience of lifting the platen in order to see what had been written.

|